Abstract

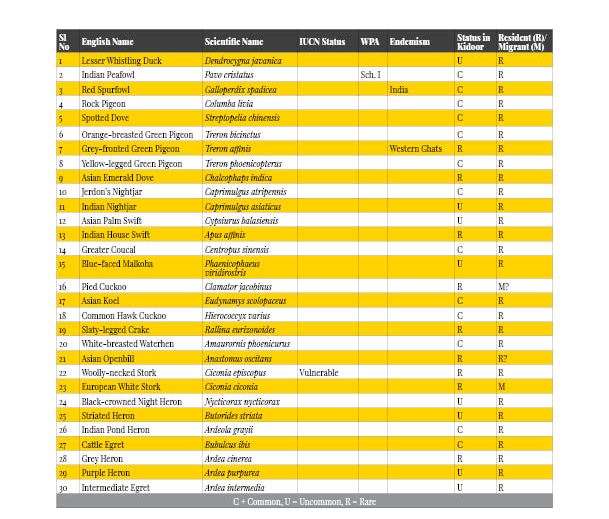

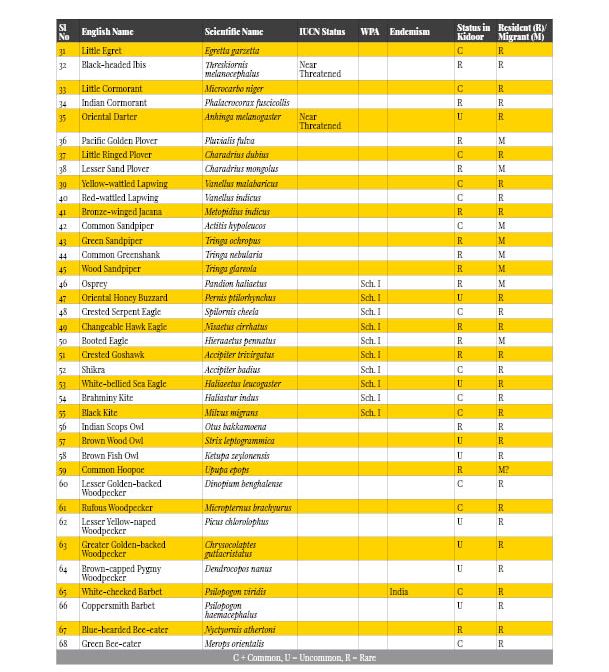

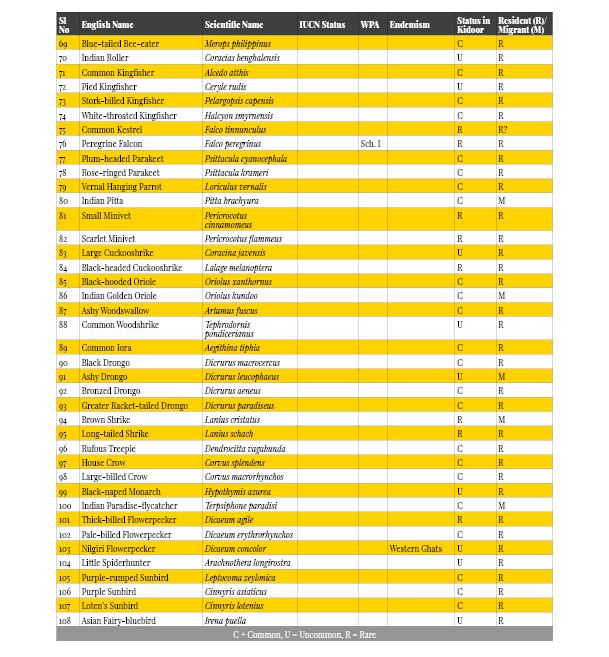

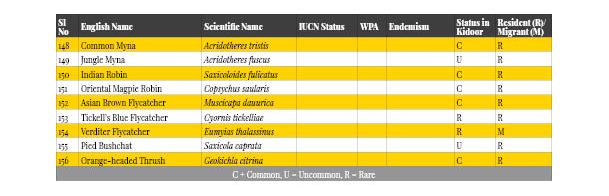

The avian diversity in Kidoor, Kasaragod district of north Kerala was documented from September 2016 to December 2018. A total of 156 species belonging to 18 orders and 56 families were documented. The checklist of birds including the Orange-breasted Green Pigeon Treron bicinctus a rare and patchily distributed species in Kerala is presented.

Introduction

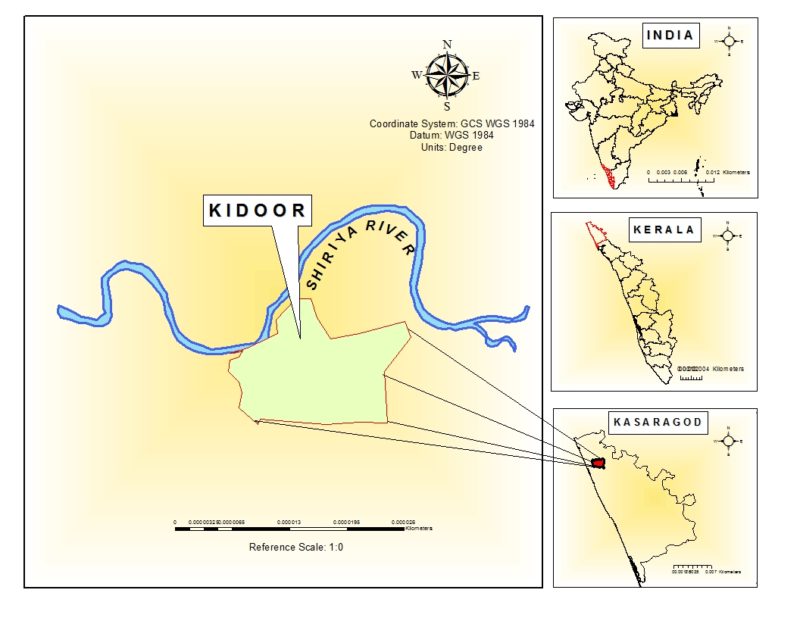

Avifauna is one among the well-studied groups of vertebrates in the world. Bird studies help in understanding the habitat and distribution of each of the species and helps in their conservation. Kasaragod district of north Kerala has extensive flat-topped lateritic areas in the midlands. This landscape has sparse vegetation and is highly heterogeneous in soil type, ecological conditions of land and other patterns (Nair, 2011). Diverse type of habitat might account for diverse type of species (Lorenzon et al. 2016). Studies on species diversity are essential to understand the health of the ecosystem, which will help to plan conservation strategies for this unique ecosystem. This habitat does not come under any protected area network. In recent years, some studies were done in the field of avian diversity of certain parts of Kasaragod district (Rodrigues, 2017; 2018). Here, an attempt was made to study the bird diversity in Kidoor village of the district.

Study area

Kidoor (12.63°N, 74.98°E) is located in Kumbla Grama Panchayath. The study area consists of lateritic plains, paddy fields, well wooded areas, arecanut and coconut plantations and wetlands including the parts of Shiriya River.

Methodology

The study was conducted by Area Count Method (eBird, 2019) from September 2016 to December 2018. Birds and their activities were recorded mainly during the morning and evening hours as well as other time of the day and some times in the night to record nocturnal species. All these observations were uploaded in eBird.org. Nikon (20×50) and Olympus (8×40) binoculars and Canon SX 420 IS camera were used for field observations and documentation. The birds were identified using standard field guides like Ali (2002) and Grimmett et al. (2011).

Results

A total of 156 species of birds were observed (Table 1), which composed of 18 orders and 56 families (Praveen et al. 2018) including Passeriformes (77 spp), Accipitriformes & Charadriiformes (10 spp each) and Pelecaniformes (9 spp). Out of the total, 152 species fall in the Least Concern category of the IUCN red List. Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus is categorized as Vulnerable and other three species are categorized as Near Threatened viz., Black-headed Ibis Threskiornis melanocephalus, Oriental Darter Anhinga melanogaster and Grey-headed Bulbul Brachypodius priocephalus (IUCN 2019).

Grey-fronted Green Pigeon Treron affinis, Nilgiri Flowerpecker Dicaeum concolor, Flame-throated Bulbul Pycnonotus gularis, Grey-headed Bulbul, Rufous Babbler Argya subrufa and Malabar Starling Sturnia blythii are the Western Ghats endemics seen here.

Twelve species of this are included in Schedule 1 of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act 1972: Indian Peafowl Pavo cristatus, Peregrine Falcon (Shaheen) Falco peregrinus perigrinator and also 10 other Accipitrids; 131 species are in Schedule 4 and one species (House Crow Corvus splendens) is in Schedule 5.

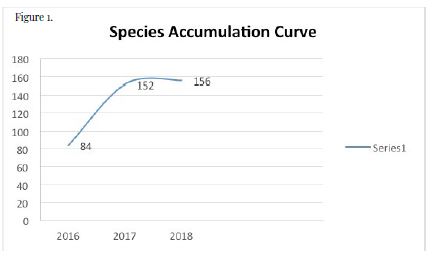

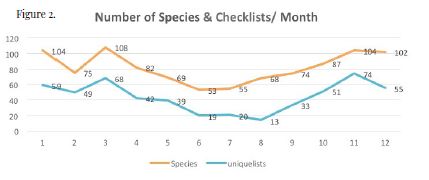

In 2016 the first year of the study, 84 species were recorded. The species count rose to 152 in 2017, indicating the good diversity of birds and also as a result of intensified birding effort; in 2018 four more species were added to the checklist. We can see a surge in the graph from 2016 to 2017, the graph then levels off indicating that almost all species of birds of the study area had been recorded (Fig. 1). But there are chances for finding some of the rare winter visitors in the coming years. The species diversity as well as checklists uploaded (effort) in each month are shown in Fig. 2. The maximum checklists were uploaded in the months from November to March. The least number of checklists were uploaded in the monsoon season during June to August. Comparatively less number of species was observed in monsoon as only the resident birds were present whereas in the winter months maximum number of species was recorded because of the presence of migratory species.

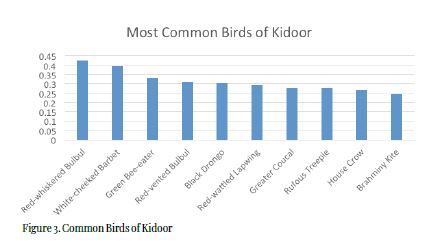

The species diversity as well as checklists uploaded (effort) in each month are shown in Fig. 2. The maximum checklists were uploaded in the months from November to March. The least number of checklists were uploaded in the monsoon season during June to August. Comparatively less number of species was observed in monsoon as only the resident birds were present whereas in the winter months maximum number of species was recorded because of the presence of migratory species.  In Fig. 3, the x-axis shows the bird species and y-axis shows the frequency i.e. the percentage of checklist in which a species is reported.

In Fig. 3, the x-axis shows the bird species and y-axis shows the frequency i.e. the percentage of checklist in which a species is reported. Red-whiskered Bulbul Pycnonotus jocosus was reported in maximum number of checklists, followed by White-cheeked Barbet Psilopogon viridis, Green Bee-eater Merops orientalis, Red-vented Bulbul Pycnonotus cafer, Black Drongo Dicrurus macrocercus, Red-wattled Lapwing Vanellus indicus, Greater Coucal Centropus sinensis, Rufous Treepie Dendrocitta vagabunda, House Crow Corvus splendens and Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus. These birds can be considered as very common in Kidoor, because they are reported in high frequency than other birds.

Red-whiskered Bulbul Pycnonotus jocosus was reported in maximum number of checklists, followed by White-cheeked Barbet Psilopogon viridis, Green Bee-eater Merops orientalis, Red-vented Bulbul Pycnonotus cafer, Black Drongo Dicrurus macrocercus, Red-wattled Lapwing Vanellus indicus, Greater Coucal Centropus sinensis, Rufous Treepie Dendrocitta vagabunda, House Crow Corvus splendens and Brahminy Kite Haliastur indus. These birds can be considered as very common in Kidoor, because they are reported in high frequency than other birds.

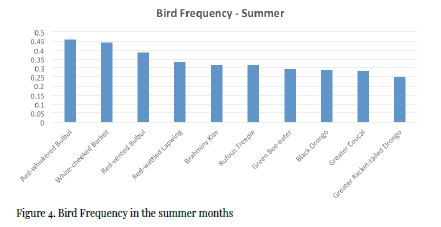

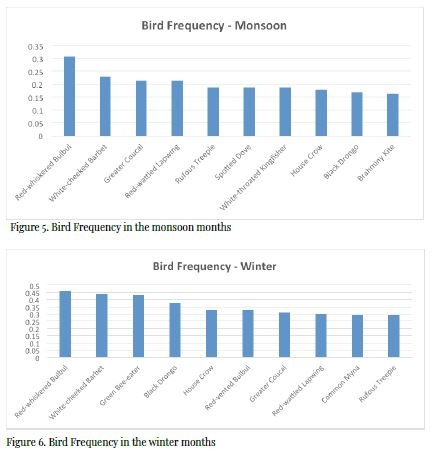

Figures 4, 5 and 6 show the frequency of some common birds in different season of the year.

Red-whiskered Bulbul and White-cheeked Barbet were the most common species in all seasons and occupied the first and second position respectively. Red-wattled Lapwing, Rufous Treepie, Black Drongo and Greater Coucal also were observed commonly in all three seasons. Red-vented Bulbul, Brahminy Kite, House Crow and Green Bee-eater were common for at least two seasons. Interestingly Green Bee-eater was not at all recorded in peak monsoon months of June to August. When this fact was cross checked with the eBird data for north Kerala and coastal districts of south Karnataka, we could find that this species occurred less frequently in the time of peak monsoon, similar trend was observed in Mysore bird atlas too (Praveen J, pers. comm. dated 13th June 2019; Bird Count India, 2019).

Red-whiskered Bulbul and White-cheeked Barbet were the most common species in all seasons and occupied the first and second position respectively. Red-wattled Lapwing, Rufous Treepie, Black Drongo and Greater Coucal also were observed commonly in all three seasons. Red-vented Bulbul, Brahminy Kite, House Crow and Green Bee-eater were common for at least two seasons. Interestingly Green Bee-eater was not at all recorded in peak monsoon months of June to August. When this fact was cross checked with the eBird data for north Kerala and coastal districts of south Karnataka, we could find that this species occurred less frequently in the time of peak monsoon, similar trend was observed in Mysore bird atlas too (Praveen J, pers. comm. dated 13th June 2019; Bird Count India, 2019).

Discussion

The status of birds was classified mainly based on the percentage of checklists in which a species was reported and also based on the field experience. If, a species was recorded in large number of checklists and seen throughout the year, that species was considered as common. If a species was observed irregularly and recorded in less number of checklists, the bird was considered as uncommon. If a species was recorded only in very few checklists, then it was considered as rare. In the case of migratory species, the same criteria were applied taking into consideration the months of the year when they were present here. at the study site. The migratory or resident status of the birds are given as per their status in Kerala.

Orange-breasted Green Pigeon, a rare bird in Kerala (Sashikumar et al. 2011) was observed throughout the year except in August and September months. This must be one of the few locations in Kerala where this species has been recorded regularly, throughout the year. However, since 2017, there were few more sightings of Orange-breasted Green Pigeons in few other locations of the district with similar habitat. Yellow-legged Green Pigeon Treron phoenicopterus was observed regularly in fruiting trees of the lateritic midland viz., Macaranga peltata, Mangifera indica, Artocarpus heterophyllus, Ficus religiosa, etc. This species was observed all through the year except in May, June and July. None of the green pigeons were seen nesting in the study area. Grey-fronted Green Pigeon and Emerald Dove Chalcophaps indica were comparatively rare.

Regarding nocturnal birds, Jerdon’s Nightjar Caprimulgus atripennis was common and Indian Nightjar Caprimulgus asiaticus was uncommon. Indian Scops Owl Otus bakkamoena was observed from September to December; Brown Fish Owl Ketupa zeylonensis was recorded in the months of February, March, May, June, October and November; Brown Wood Owl Strix leptogrammica was more common than other owls.

Slaty-legged Crake Rallina eurizonoides, an elusive bird, was recorded in the monsoon months, identified by its frog like kek-kek, kek-kek continuous call during the breeding season (Grimmett et al. 2011; Sashikumar et al. 2011, Murukesh & Balakrishnan, 2015). But on other months this bird was not seen or heard. It was clearly seen only once and on all other occasions, we could see only the silhouette of the fast flying bird when we approached the origin of the call.

When most migratory birds returned to their breeding grounds, some species over-summered in the study site. Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis fulva was observed from June to October 2017, up to a flock of 23 individuals. Lesser Sand Plover Charadrius mongolus was observed from July to September 2017, only in the lateritic patches. Interestingly, these species were not observed anywhere in the study area in winter. A few individuals of Little-ringed Plover Charadrius dubius were also found along with these two species of waders. Over-summering of these birds have been regularly reported from Madayipara, in Kannur district where similar habitat is present (Sashikumar et al. 2004). In 2017, one Indian Pitta Pitta brachyura, a migratory bird, was observed even after May till the month of July.

European White Stork Ciconia ciconia , a migratory bird, was recorded in the study area which is the only sighting of this species in Kasaragod district so far (Kidoor & Rodrigues, 2018).

During 2010-11 minimum of 15-20 individuals of House Sparrow Passer domesticus were present in the study area (Ibrahim Chepinadka, pers. comm. dated Jan 2017). But during our study period, this species was rare and four was the maximum number recorded at a time.

Breeding activities (nests, eggs or chicks) of Yellow-wattled Lapwing Vanellus malabaricus, Red-wattled Lapwing, Slaty-legged Crake, White-throated Kingfisher Halcyon smyrnensis, Common Kingfisher Alcedo atthis, Large-billed Crow Corvus macrorhynchos, Indian Robin Saxicoloides fulicatus, Shikra Accipiter badius, Coppersmith Barbet Psilopogon haemacephalus and Black-hooded Oriole Oriolus xanthornus were noted during the study period.

Plain Prinia Prinia inornata, Indian Thick-knee Burhinus indicus and Tree Pipit Anthus trivialis were recorded in nearby areas with similar habitat (Ambiladka) but have not been considered in this checklist.

Threats

Hunting of birds and other animals using traps were reported. Trap was prepared by locals for capturing Red Spurfowls Galloperdix spadicea. Lateritic rock mining, metal quarry mining, sand mining from Shiriya River, encroachment of revenue land and increased feral dog population are some of the other major threats. The fairly undisturbed lateritic landscape with its own type of vegetation in the area acts as good habitat for many ground dwelling birds and the small ponds in between acts like natural water-baths for birds and other creatures and also attracts the migratory species.

According to our discussion with the general public from the study site, the population of House Sparrow had declined over the years. Similar studies and interactions are needed to find out about the change in the population of birds.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our sincere gratitude to Ashwin Viswanathan for helping us in statistical analysis of the bird data and providing us good help and support. We thank Dhanaraj K., for providing a map of the study area. We thank all the observers who uploaded their valuable data of birds into eBird during their visit to Kidoor.

References

Ali, S. (2002). The book of Indian Birds. 13th edition. Revised by J. C Daniel.

eBird. (2019). eBird: An online database of bird distribution and abundance [web application]. eBird, Ithaca, New York. Available at https://help.ebird.org/customer/en/portal/articles/1006209-understanding-observation-types (Accessed on 16 June 2019).

Bird Count India. (2019). Mysore Bird Atlas. https://birdcount.in/mysore-bird-atlas/ Accessed on 19 June 2019.

Grimmett, R., Inskipp, C. & Inskipp, T. (2011). Birds of the Indian Sub-continent. Second Edition. Oxford University Press.

Kidoor, R. & Rodrigues, M. (2018). Sighting of White stork Ciconia ciconia at Kidoor, Kasaragod District. Malabar Trogon Vol. 16 (2): 20-21.

IUCN. (2019). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2019-1. http://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 21 March 2019.

Lorenzon, R. E., Beltzer, A. H., Olguin, P. F. & Virgolini, A. L. R. (2016). Habitat heterogeneity drives bird species richness, nestedness and habitat selection by individual species in fluvial wetlands of Parana River, Argentina. Austral Ecology 41: 829-841.

Murukesh, M. D. & P. Balakrishnan. (2015). On the breeding of the Slaty-legged Crake (Aves: Rallidae: Rallina eurizonoides) in Nilambur, Kerala, Southern India. Journal of Threatened Taxa 7(6): 7298-7301; http://dx.doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o4185.7298-301.

Nair S Sathis Chandran. (2011). The changing landscape of Kerala. In: Sashikumar. C., Praveen J., Palot M. J., Nameer P. O. (Eds) Birds of Kerala status and distribution. DC Books, Kottayam, 30–53p.

Praveen J., Jayapal, R. & Pittie, A. (2018). Checklist of the birds of India (v2.2). Website: http://www.indianbirds.in/india/ [Date of publication: 31 July, 2018].

Rodrigues, M. K. (2017). Avian diversity of Bengapadav, Kasaragod district, Kerala. Malabar Trogon Vol. 15(1): 46-49.

Rodrigues, M. (2018). Birds around the paddyfields of Aranthode. Malabar Trogon Vol. 16 (1): 25-32.

Sashikumar. C., Palot. M. J., Meppayur. S. & Radhakrishnan C. (2004). Shore birds of Kerala, Including gulls & terns. ISBN: 81-8171-047-9.

Sashikumar, C., Praveen, J., Palot, M. J. & Nameer, P. O. (2011). Birds of Kerala: Status and Distribution. Kottayam, DC Books.