Abstract

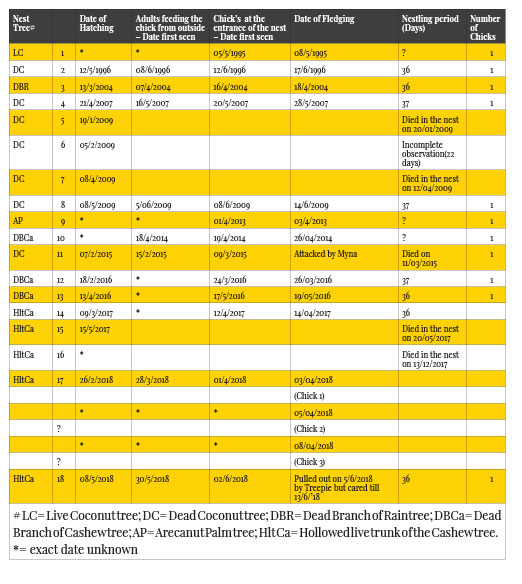

This paper describes the breeding and nesting activities of the White-cheeked Barbet Psilopogon viridis based on a total of 18 nests that were observed between 1995 and 2018. It was assumed that the pairs observed are either the same pair breeding in successive seasons or a new pair that took over the territory of the original pair. Some of the observations made were thus: The breeding pair built a new nest or reused the old nest. The pairs had their second or even a third brood in a season if there were nest failures. But they also had a second brood if they had their first brood very early in the season. The parent birds abandoned the unfledged chicks that fell out of the nest accidentally or when the nest was attacked by other birds or animals but continued to raise them if they were replaced in the nest. On the day of fledging, the chick was taken to a new roosting nest in the evening.

Introduction

Asian barbets are found in the well-wooded landscapes in South and Southeast Asia. According to recent systemic revisions based on morphological and molecular evidence (Moyle, 2004; Feinstein et al., 2008; Tex and Leonard, 2013), apart from the genus Calorhamphus (two species), the family Megalaimidae embeds the genera Psilopogon (one species) and Megalaima (31 species) which are now placed by certain authors within the genus Psilopogon (Dickinson & Remsen, 2013; Trounov & Vasilieva, 2014).

Nests of hole-nesting birds are difficult to observe in comparison to other groups of birds. But in a few barbet species such as White-cheeked Barbet Psilopogon viridis and Crimson-fronted Barbet Megalaima rubicapilla in India (Yahya, 1989; 2001) and the endemic Taiwan Barbet M. michalis (Koh & Lu, 2009; Lin et al. 2010), successful methods have been used to observe nest activities inside the nest holes.

White-cheeked Barbets are mostly frugivorous and are important pollinators and seed dispersers. They are seen mainly along the Western Ghats south from the Surat Dangs and along the associated hills of southern India into parts of the southern Eastern Ghats mainly in the Shevaroy and Chitteri Hills. The only publications available regarding the breeding of the White-cheeked Barbets are that of Yahya, H.S.A (1989; 2001).

Materials and Methods

No intrusive methods were used to observe the contents, residents or activities inside the nest cavity. The instruments used were a pair of binoculars, a Nikon camera, a time watch, and a measuring tape. Daily observations were made in the morning and in the evening, viz., from 0515 to 0600 h; 0630 to 0800 h and from 1700 to 1900 h. Further infrequent observations were made between 0800 h and 1700 h. The hatching date was calculated by observing the behaviour of the parent birds and from the sighting of the eggshells on the ground below the nest. It was not possible to know the exact date of egg laying and the number of eggs laid by observation alone as one of the breeding pair (probably the female) began roosting in the nest hole in the night even before the nest building was complete and the pair took shifts in guarding the nest against other hole nesters many days before the eggs had been laid. The study was carried out from 1995 to 2018 during which period a total of 18 nests were observed.

Study Area

The nests were located within a half-acre plot in Mayyanad, a suburban region near Kollam city in Kerala, India (8.84 N and 76.6 E). The plot contained more than 100 trees and shrubs of various species. Fruits and berries were available in all seasons. The sunrise was at 0650 h and sunset at 18 25 h in January and in May, the sunrise and sunset were at 0600 h and 1840 h respectively. The South-West Monsoon occurred from June to August with occasional summer showers from March. The North-East Monsoon was during October-November months.

Nest Searching

Searches for paired barbets and their nests were based on visual as well as auditory clues and nests were located by following the adult birds. The sex of the adults was ascertained by observing their positions during copulation and was identifiable by the key features between individuals in the pairs of nest nos: 3, 5, 6, 7 & 8. Not more than one barbet pair bred in the half-acre study plot at a time but nests of other pairs were noticed in the neighbouring plots. However, those nests were not included in the present study. The minimum distance between two nests was 50 meters.

The nests for description were obtained from the samples of old nests when the rotten tree fell naturally or from a new one when the tree was cut down.

Various trees were used by the barbets as nesting trees, although a majority of them were that of dead coconut Cocos nucifera. Sometimes dying Arecanut trees Areca catechu were also used. Even appropriate dead branches of species like Rain Tree Albizia saman, Cashew Anacardium occidentale, Indian Laurel Ficus microcarpa, etc., as well as the live trunk of a Cashew tree with a rotten core were used for nest building.

Results

Breeding Season

Breeding season in Mayyanad mostly occurred between December and July and this time period concurs with Yahya (1989), who studied this species in Periyar Tiger Reserve.

Identification of Birds

White-cheeked Barbets (mentioned as barbets hereafter) are greenish in colour with white-streaked brownish head and chest. They have a distinctive white supercilium and a broad white cheek stripe below the eye and a pale pinkish bill. However, I had found a pair with a slight difference in the colour during my study. The feathers on the back of the male bird were bright green whereas the female had brownish green colour. She had a darker brown head also. These differences could be easily observed in good daylight and at close proximity, when the birds were mating or sitting together. I was able to observe them at a very close distance of 2.5m in 2004 in the case of nest no: 3 and at a distance of 6m in the case of nest nos: 5, 6, 7 & 8 in 2009 (Table 1) from the terrace of my house. I am not absolutely certain that the female bird of nest no: 3 and the female bird of nest nos: 5, 6, 7 & 8 were the same; but the birds became used to my presence on the terrace even before they started building their nests.

Calls

During the breeding season, the barbet calls became loud and constant, especially in the mornings and evenings. The calls are either kotroo kotroo or kuroo kuroo starting with an explosive kurrr. Both male and female birds made these two types of calls. When the male produced the kotroo call, the female responded with the kuroo call with the explosive kurr. When the female cried kuroo, the male responded with the kotroo with an explosive kurr. Sometimes the male or female bird responded without the explosive kurr. One barbet’s call triggered other barbets in the neighbourhood to call. After the hatching, the parents became more or less silent and only made occasional kuk, kuk notes. The parent birds resumed their kotroo calls a week after the fledging of the chick. Kirrr kirrr notes were used when the adult bird communicated with its mate or when chasing away other barbets or birds like mynas and koels. During the incubation period, the female bird occasionally made kueee kueee notes when leaving the nest. Khe khe calls were used when the adult bird warned the chick about some danger. The parent barbets which stopped making their usual kutroo call after the hatching of the chick started making this call again a week after the fledging of the chick.

The chick’s calls

The chicks made loud sounds during feeding or when the adults were removing the faecal sac. Some chicks were very silent and some very noisy between the feeding time. Some chicks made tirr tirr or kirr kirr or kud.d.d kud.d.d sounds initially but a few days before fledging chicks started making kutroo kutroo calls continuously, i.e., before, during and after feeding.

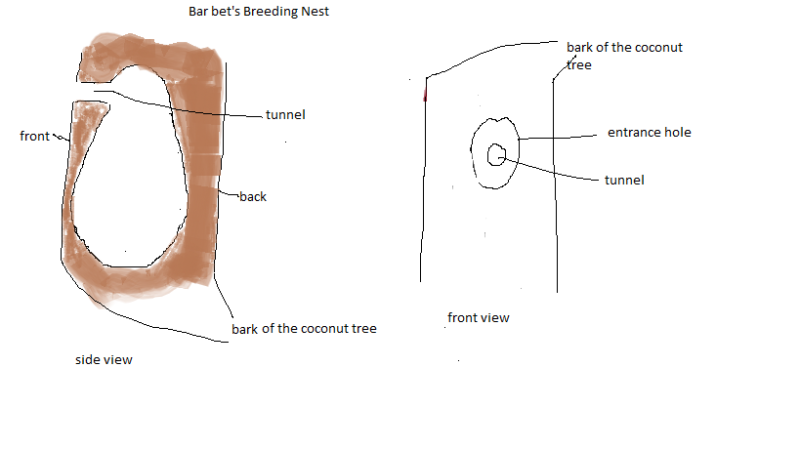

Nest description

The height of the nest hole from the ground was between 6.6 and10 m (20-30 ft). The nest was made by excavating a hole in a dead or dying tree trunk, on a dead branch of a tree or in the rotten core of a trunk in a live tree. Both the partners worked together in nest building. During nest building, the relieving partners fed the working mates. Yahya (1989) had made similar observations with regard to this behaviour. But sometimes the male does most of the work (Yahya, 1989) and for more than one hour with a few minutes of rest in between. This happened when their original breeding nest tree was cut down. If the wood was soft, the birds completed the excavation in a few days. But if the wood was hard, it took more than a month’s time.

A newly dead trunk of a mature coconut tree has wood which is very hard for the barbets or the woodpeckers to build a nest hole. The dead tree thus remains unused for two or more years before these birds begin building their nests in it. The barbets first started building a nest on the top of the tree where the wood is softer than the trunk. But it was mostly a roosting nest than a breeding nest. In this case, the height of the roosting nest hole was about 16.6-20 m (50-60 ft) high (Colonel E. A. Butler, mentioned in Hume, 1890). A breeding nest was usually built towards the middle part of the trunk where the circumference of the trunk of the tree was larger than the top portion.

If the pair did not find a suitable tree for nest building in a season, they searched for one in the neighbourhood or fought with another pair for their breeding nest; sometimes they waited for another pair’s chick to fledge as in the case of the pair in nest no: 13 in 2016 (Table 1) where the pair took over the nest on the same day the chick fledged from the nest. Every breeding season I noticed barbets fighting for the breeding nest. Again, this observation is in accordance with Yahya (1989).

The barbets built two types of nests: one for roosting and another for breeding. The structure of these two nests was different. They used the breeding nest during the non-breeding time for roosting, but never used the roosting nest for breeding purpose. If the breeding nest was in good condition then the birds used it for two successive breeding seasons mostly and rarely as in case of the nest built in the cashew tree trunk, for three breeding seasons from 2016 to 2018. In 2016, the nest was built on a small dead branch of a cashew tree, when the branch became rotten in the rain and fell off and thus exposed the nest’s extension into the tree trunk. In 2017, the birds dug deeper into the tree trunk and used the nest in 2018 also. But in 2019, as the woodpeckers widened the entrance hole, the barbets abandoned the nest. There were more roosting nests in the area than breeding nests. When a barbet entered the roosting nest in the late evening and finds it already occupied by another barbet or bird or a squirrel, they immediately flew out of the nest to go searching for another unoccupied nest in the neighbourhood. Only once did I find a barbet sitting on my window grill in the night, either from being pushed out of its roosting nest or failing to find an unoccupied nest. But it flew away into the darkness on seeing me unexpectedly. Juvenile barbets made very shallow roosting nests for themselves. For breeding, the adult barbets selected the tree for nest building very carefully (see below) and defended the breeding nests from other hole nesters like Common Myna Acridotheres tristis, Jungle Owlet Glaucidium radiatum, Black-rumped Flameback Dinopium benghalense and other White-cheeked Barbets. Black-rumped Flamebacks did not breed but only roosted in the barbet’s nest after enlarging the entrance. I have observed woodpeckers fighting for a barbet’s roosting nest daily during a South-West monsoon season. Flamebacks usually built their own breeding nests.

Nest site selection and excavation

Breeding Nest: For building a breeding nest, the barbets selected a tree which had some canopy cover around the nest hole, probably for the protection of the nest from predators and for the safety of the chicks when they take the first flight. They did not build a breeding nest in an isolated dead coconut tree trunk in a barren land or in coconut groves where there are only coconut trees; but occasionally made roosting nests on such isolated coconut trees. I have observed barbets making breeding nests on coconut trees only in plots where there were many other trees along with coconut trees. At a suitable position, about 6.6-10m (20-30ft) height, they pecked the dead tree or branch to make a small hole for the entrance of the nest. The entrance hole of a breeding nest on a coconut tree faced either towards the south, south-west or south-east only. This could be to avoid the winds during the South-West monsoon rains which blow initially from the west and the north. The entrance hole on an inclined dead branch of a tree will be under the branch and was found facing towards the north as the inclined branch protected the nest from the rain. It seemed that there was no relationship with the position of the entrance hole and the bird’s territory. Breeding nests were mostly seen in coconut trees (N = 8), three nests were seen in cashew tree and one each in a Rain tree and an arecanut tree.

Roosting Nest: The entrance hole of a roosting nest was not built facing any particular direction. Barbets, while excavating the nest, collected the wood dust and chips in their beak and tossed them sideways to the ground below the nest tree when it worked at the entrance hole. But when the nest building was in an advanced stage, the birds collected the wood dust and chips in their beaks and flew to a nearby tree branch and jerked their head sideways to spit out the wood dust. In three coconut tree trunks, there were a breeding nest and roosting nest on the same tree. In the case of the pair in which sexes could be identified, the male usually slept in the roosting nest and the female used the breeding nest for roosting. Roosting nests (N = 14) were found mostly in coconut trees (10) and one each in a fig tree, jack tree, mango tree Mangifera indica, and Subabul tree Leucaena leucocephala.

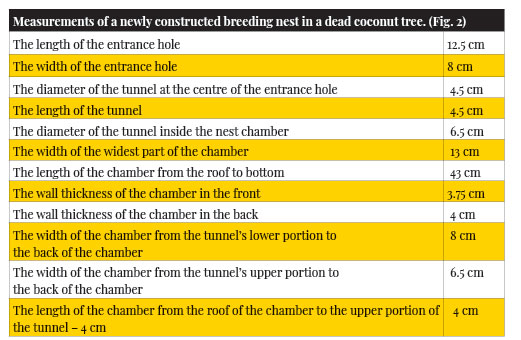

Most of the roosting nests (N = 5) on a coconut tree that I found were in a very rotten state after Common Mynas, Jungle Owlets or Black-rumped Flamebacks had used them many times. The nest chamber was in the shape of a flask. From the entrance hole to the bottom, the chamber was 30 cm in depth. The inside of the chamber was very smooth. The front portion of the nest chamber consisted only of the bark of the coconut tree. The back wall of the chamber was thick and tapered towards the front. The entrance hole of the chamber was situated at the top part of the chamber where the unexcavated trunk of the coconut tree met the excavated thin bark of the chamber. The entrance hole of the roosting nest was very small (4.5cm in diameter) compared to the hole of the breeding nest. It did not have a tunnel that led to the chamber as in the breeding nest. It directly entered into the chamber. Because of the smallness of the entrance hole, it can easily be mistaken as those made by beetles. The entrance hole did not have the worn look of a breeding nest hole. It thus protected the nest from the predators to some extent, but not from the Black-rumped Flameback or the Common Myna. The widest part of the nest was just above the bottom of the nest chamber, which was approximately 16cm in width. The bottom part of the nest was bowl or saucer shaped. The barbets did not use this nest for breeding purpose.

Roosting nest on a branch of a dead fig tree (Ficus microcarpa): The circumference of the branch was 32.5cm. The entrance hole was directed towards north. The diameter of the entrance hole was 4.5cm. There was no tunnel to the chamber. The depth of the flask-shaped chamber was 30 cm. The wall thickness at the back was 2.5 cm and in the front was 1.5 cm. The width of the chamber at the widest part of the chamber was 9 cm. The bottom part of the nest was bowl-shaped.

Coconut tree

Structure of a White-cheeked Barbet’s breeding nest in a Coconut tree: Most of the breeding nests that I found were in a rotten state except one that was newly constructed but this nest tree was cut down before the birds could breed in it. The breeding nest chamber also was flask-shaped (retort-shaped, as mentioned by Hume, 1890) and had a thick wall around it. So the chamber was smaller than that of the roosting nest but had very smooth walls around. The entrance hole led to a tunnel at its centre through the thick wall and gave way to the chamber. The wall of the chamber was thickest around the tunnel portion and thinnest just above the bowl/saucer-shaped bottom portion of the chamber. The back of the chamber was thicker than the front. The tunnel was funnel-shaped. i.e., the opening of the tunnel inside the chamber was wider than the opening near the entrance hole.

Sleeping pattern of a pair of barbets

In the case of one particular pair of barbets observed in 2009 where I could individually identify the male and female birds, in the non-breeding as well as in the breeding time, before the eggs hatched, both the male and the female birds made their evening round of calls before entering their respective nests for roosting. They entered their nest only when it was completely dark. The male bird usually entered the nest much earlier than the female. The male bird entered the nest very quickly. The female usually waited until it was very dark (1830 h in January and 1900 h in May) and made sure that no other bird or animal saw her entering the nest. If she felt that some bird or animal had seen her entering, she immediately came out of the nest and made kuk- kuk sound and waited till it was safe. She entered the nest slowly, first clinging to the entrance hole and putting her head in and out of the tunnel many times before entering. The male and female birds (breeding pair) sometimes slept in different nest holes on the same tree. In the morning when it was still dark (pre-dawn) (05 45 h in May and 06 30 h in January) the barbets left their nests and welcomed the morning with their calls. Sometimes after feeding during the daytime, the male and female birds entered their nest for roosting or relaxing by sitting at the entrance.

Courtship

In the pair observed in 2009, the male bird fed the female during courtship and incubation periods. Yahya (1989) also had recorded this behavior. The male passed an insect or fruit to the female by holding it at the tip of his beak. The female took the food from the beak and swallowed it. He never put the food inside the female’s mouth. The female did not show any begging gestures when receiving food from the male. During courtship, the male sometimes rubbed the female with his head and body and preened her feathers. Trounov & Vasilieva (2014) also noted this in their study of Red-vented barbet, Megalaima lagrandieri in Loc Bac forest in Lam Dong Province of southern Vietnam.

Copulation

I was able to observe the copulation of the barbets on nine occasions. No courtship rituals were noticed before mating. Courtship feeding by the male was not observed before or after copulation. Usually, the male bird flew to the female that was sitting on a branch and mounted. During mating, they neither fluttered their wings nor called; Yahya (1989) had observed fluttering of wings during mating. After copulation which lasted only a few seconds, the male flew to a nearby branch while the female remained at the same spot. A moment later, the male returned to the female to mate for a second time. This second attempt was observed on all the occasions. Yahya (1989) and Trounov & Vasilieva (2014) had also observed the same. After mating for the second time, the female was the first to leave, by flying out, from the mating position. She flew to a nearby branch and the male flew away to a distant tree to call out kutroo kutroo. Copulation was also observed once (nest no: 3) while there were chicks in the nest. A similar observation was made by Yahya (1989).

Egg-laying and eggs

I did not inspect live nests for its contents as the description of eggs and details of clutch size are already available in published literature. Eggs are white in colour without gloss. They are elongated, having a distinctly blunt and a pointed end (Yahya, 1989; Baker, 1934) or oval shape (Pande, 2004). The average size of the egg is either 26.20×20.30mm (Baker, 1934; Pande, 2004) or 29.01×20.6mm (Yahya, 1989). The approximate date of egg-laying was calculated by subtracting 15 days from the date of hatching. Number of eggs in each brood is three according to Yahya (1989) and Hume (1890) but according to Ali (1970) and Baker (1934), it is four.

Incubation period

For the activities of the parents inside the nest during incubation and the chicks after hatching I rely on Yahya (1989) and Lin et al. (2010).

The average incubation period is 14-15 days (Yahya, 1989; Ali, 1970). The night incubation and night brooding were done by the female alone. In the nest nos: 3, 5, 6, 7 & 8 where I was able to watch the nest from the terrace of my house, I saw the male take up its duty in the morning when it was still dark. In December-January, it was at 06 30 h and in April-May at 05 45 h. Before he came to the nest site, the male made a loud kutroo – kutroo call from his roosting tree. Ali (1964) and Blanford (1895) have noted that barbets may call in the night during the breeding season. After his loud call, the male silently came to the nest tree or a nearby tree and then flew to the entrance hole and softly called out Kirr Kirr to the incubating female. Immediately, the female flew out of the nest silently. Then the male entered the nest and started incubating the eggs until the female returned in about 20- 30 minutes. In the later shifts during the day, the male before taking up the shift, sometimes announced his presence by calling kutroo kutroo from a nearby tree and the female left the nest making kuee kuee call and then flew to a nearby tree to call out kuroo kuroo without the initial kurrr sound. During the hot part of the day, the incubating bird was observed to sit at the entrance with its head outside the nest hole. In the late evenings, both the male and female made kutroo calls before they entered their respective nests for roosting. The parents spent more time on incubation during morning hours and on a rainy day when the atmospheric temperature was low. Yahya (1989) also had observed similar behaviour in his study.

Hatching

The eggs hatched on a ‘first-laid-first-hatched’ basis (Yahya, 1989). After hatching, both male and female became almost silent except for occasional kuk kuk sounds. The morning after hatching, the female did not wait for the male to relieve her from the night brooding. Instead, she flew out of the nest when it was still very dark. i.e. at 0625 h in January and 0540 h in May. This gave the clue that the eggs had hatched. Presence of eggshells on the ground below the nest was another indication that the eggs had hatched. After hatching, each day, she left the nest earlier than on the previous day. Visibility being very poor at that time, only the shadow of her flying out of the nest could be ascertained. She returned to the nest a few moments later but it was very difficult to see whether she brought food for the chick.

Nestling period

The average nestling period is 36 days based on the information I could gather on the 10 chicks out of the 14 that I studied. Each day after hatching, the female delayed her roosting time later than the previous day. So the roosting time of the female on the night before the chick fledged in May was well past 1900 h. While all the diurnal birds had already settled for roosting, the parent barbets still fed the chicks despite the darkness. Because of low visibility, I was not able to note whether the female roosted with the chick on the night before the chick fledged.

Feeding and nest sanitation

The observations made for feeding and nest sanitation is based solely on specific nests which I was able to observe closely, namely nest nos: 3, 5, 6, 7 & 8. I could see that in the first few days after hatching, the parent birds brooded the chick for 5-10 minutes after feeding. Yahya (1989) too had noted this. When the weather was cold, either of the parent birds brooded for about 20 minutes. As the chick grew, it was fed every two minutes continuously for 30 minutes to one hour in the morning between 0600 h to 0800 h. If there were any winged termites nearby, the chick was fed 3-4 times every minute for 30 minutes or more. After 0800 h, the feeding frequency was reduced and in the midday and afternoon, the parents relaxed on a nearby tree until 1600-1630 h; then the feeding increased and lasted till late (1900 h) in the evening. Only occasional feeding was seen during the relaxing period. If there was heavy rain and the parents could not find insects, they gave the chick a fruit diet. The male and female took an equal share in feeding the chicks. But the male bird brought more fruits than insects for the chick. On the first one or two days, the food items were very small or regurgitated food and as the chick grew, so did the size of the given insects and fruits. On the 3rd day of hatching, very small pieces of fruit were given to the chick for the first time. I never saw the parents feeding the chick fruits on the first day of hatching as observed by Yahya (1989). Trounov & Vasilieva (2014) had observed that the parents gave plant matter from the second day onwards after hatching of the chick. Food items were small insects, grasshoppers, winged termites, beetles, caterpillars, fruits of banana Musa sp., papaya Carica papaya, custard apple Annona reticulata, guava Psidium guajava, jackfruit Artocarpus heterophyllus, wild jackfruit Artocarpus hirsutus, mulberry Morus nigra, Indian mulberry Morinda citrifolia or other wild fruits and berries. The barbets were not strictly arboreal foragers. If they found any insect or fruit on the ground, they flew to a bush nearby and then slowly descended to the ground and hopped like babblers towards the morsel, picked it up and flew to a nearby tree to eat it or if it was an insect, smashed it on a branch and took it to the nest for the chick. From the second day onwards, the parent birds started removing the chick’s fecal sac. Trounov & Vasilieva (2014) observed that the fecal sac was removed for the first time on the fourth day of hatching. At first, both the parents went inside the nest to feed. Later, one of the parent birds (male?) started feeding the chick from outside while its partner (female?) went inside to feed and remove the fecal sac. A few days before fledging, both parents fed the chick from outside. But one of the parent birds (female?) went inside the nest after every feeding session to remove or to check for any faecal sac in the nest. In nest nos: 3, 5, 6, 7 & 8, where the female bird could be differentiated, she alone removed the fecal sac. Yahya (1989) too had observed in one of his selected nests that only the female bird removed the faecal sac. When the chick was on fruit diet alone, there was no faecal sac as the excreta was passed in a semisolid state; only when the chick ate insects, there were faecal sacs which were white in colour. The semisolid excreta without faecal sac could be the reason for the foul smell in a barbet’s breeding nest, as observed by Yahya (1989) and Hume (1890).

When the chick grew older the adult birds fed the chick by holding out the food instead of putting it inside the chick’s mouth. The chick took the food from the adult bird’s beak and swallowed it. If it was a large piece of fruit or a large insect, the adult held the food item in its beak until the chick pecked and swallowed the food bit by bit. The adult usually swallowed the last portion of the fruit or insect which was inside its beak. When the chick was old enough to be fed on fruits with large seeds (e.g. wild jackfruit), the chick regurgitated the seed and spat it out through the entrance hole after swallowing the fruit. Jackfruit strands were sucked up by the chick like noodles. The chick at the entrance hole never made any begging sounds or gestures to its parents while feeding like the baby chicks of other bird species even when there were other siblings in the nest.

The adults were extremely cautious while feeding the chick. When they brought food, they never went straight to the nest. Instead, they landed on a nearby tree and watched the surroundings and only when they were sure of the safety, did they head to the nest. If they saw any birds of prey like Shikra Accipiter badius and Black Kite Milvus migrans or Jungle Crow Corvus macrorhynchos near the nest, they did not feed the chick until the predators moved away. Before the parent birds left the nest, they made sure that there were no predators around the nest; otherwise, they remained inside the nest until the surroundings were free of danger. If the intruding bird was not a bird of prey but one that may attack the chick (e.g. Common Myna or Rufous Treepie), then the parent birds either chased it away or one of them remained at the entrance hole of the nest while its mate chased away the intruder. If the parent birds failed to chase away the intruding bird, they ate the food item that they brought for the chick by themselves instead of feeding it to the chick.

Fledging

Observations of nine nests in the study period (nest nos: 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 13, 17) showed that White-cheeked Barbet chicks usually fledged when they were around 36-37 days old. In nest no. 17, there were three chicks and fledging of the chicks occurred in the manner of hatching (i.e.) on different days, not all in a single day as noted by Yahya (1989). When the first chick fledged, the other chick(s) stayed in the nest. The parents fed the unfledged chicks after the fledging of the first chick. But the frequency of feeding of unfledged chicks decreased corresponding to the number of chicks fledged. I have seen parents feeding vigorously the unfledged single chick well beyond 1900 h but when there were more than two chicks in a nest, the last chick was not fed in this manner. So the last chick might be half-starved when its time arrived to fledge. Most of the chicks fledged in the morning between 0730 h – 0900 h. On 28/05/2007 and 13/06/2018 at nest no: 4 and nest no: 18 respectively, fledging was delayed due to rain in the morning and the chicks fledged between 1400 h and 1500 h in the afternoon when there was sunshine. On the day of fledging, in every case, as Yahya (1989) also noted, the parent birds did not feed the chick in the morning. This was a very important sign to note because it helped me to know that the chick is going to fledge on that day. When the chick was ready to fledge, the parent birds made kuk kuk calls from a nearby tree as if to urge the chick to fly to the nearest branch of a tree. The chick stretched itself out of the nest and selected a branch and then took a straight flight to the branch with confidence and then hid within the foliage. On the first day, the chick took only small straight flights. It was very difficult to find the chick once it hid inside the canopy. It did not make any sound or begging gestures for food when the adult birds fed it. Only the movements of the adult birds revealed the whereabouts of the chick. The parent birds did not feed or even come near the hiding chick if they sensed any danger. In the evening, the parents slowly guided the chick away from the breeding nest to its roosting nest, which was not very far away. The roosting nest of the chick was either a new one excavated by the parents or an old one used by the parent birds, whichever was closer. The chick stayed in the new nest alone on the first night. One of the parent birds (female? – Mothers are more patient!) coaxed the chick to stay in a new roosting nest, its mate (male?) taking no part in it even though it remained nearby. I have observed this in two cases, once in nest no: 2 (1996) and another in 2008 where the parent birds nested in the neighbouring plot and brought their chick to the study plot where they made a new roosting nest for the chick on a coconut tree. For some chicks, this change was difficult. In such cases, the female (?) bird had a very hard time to settle the chick in the nest as in the case of the chick of nest no. 2. The parent birds took the chick to their previous year’s breeding nest. The female (?) bird made kuk kuk call from a tree near the roosting nest. Then the chick also made the kuk kuk call from another tree and flew to the parent bird. When it was almost dark, the female (?) bird entered the roosting nest. The chick flew to the entrance hole and clung to it and made a soft sound. Immediately the female (?) bird came out of the hole and flew to a nearby tree and the chick entered the nest. Then the female (?) bird flew back to the entrance hole; soon the chick came out of the nest and clung to the entrance hole beside the parent bird. The female (?) bird again coaxed the chick to get inside the nest. As soon as the chick entered the nest, the bird put its head inside the nest hole to push the chick into the chamber. This was repeated many times. Then it went inside the nest and came out of the nest backward; this again was repeated 3-4 times until it was sure that the chick had settled in the nest. The parent bird then flew to a nearby tree and waited until it was very dark and then both the parent birds flew to their roosting nests. One of the birds used the breeding nest to roost after the chick fledged. The distance between the breeding nest and the chick’s roosting nest in the above case was around 40 m but there were lot of trees in between. The next morning around 0800 h one of the parent birds (female?) returned to the chick’s roosting nest tree. Then the chick came out of the nest. The female(?) started preening its feathers and the chick also started preening and defecated. After that, the parent bird flew to a distant tree with the chick following.

In 16 out of 18 cases that were observed, only one chick fledged from a nest. This contradicts with that of Yahya’s observation (1989), where he mentions that two or more chicks fledged from every brood. This difference may be due to the fact that Yahya’s study area was in a forest habitat with better resource availability viz., fruits and insects.

Post-fledging period

After the chick fledged, the breeding nest was either used as a roosting nest or as a breeding nest in the same season for a second brood by the same parent birds or by a new barbet pair that occupied it. In rare cases, the adult birds permanently or temporarily closed the entrance hole and the tunnel of the nest with wood chips and wood dust. I have seen this happen on two occasions: one was at nest no: 4 (2007) where the parent birds closed the breeding nest after the chick left the nest and in another case in 2009, the male reopened the old roosting nest – which was excavated in 2008 for their chick of the previous brood to roost after it fledged, to use it as his roosting nest while the female was with the chick in the breeding nest on the same coconut tree.

For the first week or so, the male and female birds fed the chick. After that, one of the parent birds (male?) stopped feeding the chick but accompanied the other parent bird (female?) and the chick at a distance. In the nest no: 2, every evening for nine days, one of the parent birds (female?) accompanied the chick to the roosting nest and waited till the chick settled in the nest. On the 10th day of fledging, the chick went to the roosting nest alone in the evening. On the 20th day, the chick was found making a failed attempt to catch an insect in the foliage. The chick was still being fed by one of the parent birds (female?) then. On the 24th day I saw one of the parent birds (female?) and the chick near a guava tree where many adult White-cheeked Barbets were feeding on the fruits. The parent bird ate guava with other adult birds while the chick waited in a tree nearby about 7m away. When the adult barbets left the tree, the chick had its guava meal alone while the parent bird waited. On the 37th day, the parent bird and the chick were seen on a rose-apple tree. They ate the fruits together but the chick appeared totally independent and flew away by itself after eating the fruit. In Yahya’s observation (1989), the parents and chicks separated 2-4 days after fledging. But I have noticed many parent and juvenile barbets together for more than three weeks. Only after a week did one of the parent birds (male?) stop feeding the chick. In the last observed chick of nest no: 18, I was able to observe the parent and the chick together after fledging for nearly a month because the chick fledged towards the end of the breeding season.

Breeding success and failure

The barbets will go for a second (Yahya, 1989) or rarely even a third brood if they fail to fledge at least a single chick in a season. If the conditions (availability of food, good weather and undamaged nest) are favourable and the parent birds are experienced, they may have a second brood even if they had a successful first brood early in the season.

Nest defense

My study showed that, during the breeding period, the barbet pair in a territory fiercely defended their nest from other White-cheeked Barbets. But once a pair raised a brood successfully, they may forgo the now empty nest to a new pair without much fight.

Barbets defended their nest by chasing away the other hole-nesting birds like Common Mynas, Jungle Owlets, etc. They also chased away male and female Koels Eudynamys scolopaceus from the nest tree. Black-rumped Woodpeckers tend to destroy the nest by enlarging the entrance hole and the tunnel leading to the chamber thus making the chicks vulnerable to predators like Shikra and Jungle Crows. The barbets were completely defenseless when the woodpeckers attacked the nest. Three-striped Palm Squirrels also destroyed the nest wall making the nest vulnerable to attacks on eggs and chicks. They gnawed the front wall towards the lower portion of the nest where the wall was the thinnest. Sometimes the squirrels usurped the nest for breeding and filled the nest with plant fiber. Common Mynas sometimes damaged the nest wall further, already damaged by the squirrel. When the squirrel left the nest after gnawing away certain portion of the nest, the mynas pecked the gnawed part of the wood. Because the wood was soft they easily made a hole through the wall. In nest no: 11 which was thus damaged, there was an unfledged chick more than four weeks old and the mynas attacked the chick causing it to jump out of the nest. In this case, the barbet parents did not defend their nest or chick from the squirrel or mynas. The chick was later killed by our dogs. On the other hand, at nest no: 2, the barbet parents defended the nest and the chick from mynas very fiercely. At nest no: 18, a Rufous Treepie attacked the unfledged chick. When the treepie landed at the unguarded nest hole, the chick put its head out of the entrance hole probably thinking that it was the parent and the treepie pulled the unfortunate chick out of the nest. On the ground below the nest no: 13, a dead nestling with slit eyes and pin feathers on the wing and tail tip and bare skin on other parts was found on 30/04/2016. There were purplish black discolouration on its abdomen and back. The throat was swollen and red and the beak remained open. It was not clear if the chick was attacked by its sibling or whether the death was caused by any other reason.

From my observations, I deduced that unlike other birds such as crows or mynas, the barbet parents did not look after nestlings when they fell out of the nest. Even newly fledged chicks, if fallen, were not taken care of. This could be because the chicks were not fully feathered as nestlings – the skin of the throat, nape, neck, armpits, abdomen and legs were naked or sparsely feathered. The chick might not have survived the cold night or the early morning, outside a warm nest hole. Even adult birds did not roost on open tree branches. In rare cases, the adults have been found to spend the night in a depression in a jagged stump if it failed to find a roosting hole (Neelakantan, 1964). Unless the chick somehow reached the nest hole by the evening the chances are very poor for its survival. Unlike woodpecker chicks that are usually fully feathered from an early stage, the barbet chicks are incapable of climbing steep tree trunks or sleeping on tree branches. I have observed a Black-rumped Flameback chick, which jumped out of the nest a week before fledging probably because of mites inside the nest, climb a 20m (50- 60ft) tall coconut tree and sleep on a leafless teak tree during the night. It was looked after by its parents, especially by the female bird during that whole week until it was able to fly with its parents. In the barbet’s case, if the chick was returned to the nest, preferably on the same day itself, there were chances that the parents will look after the chick. But if the cause of the mishap still persisted, it was no use returning the chick to the nest. I found that on 05/06/2018 an unfledged 28-day old chick from the nest no: 18 was pulled out of the nest by a Rufous Treepie and upon returning it to the nest on the same day, it was again pulled out by the treepie. The barbet parents did nothing to defend their chick. But when I looked after the chick in an open balcony and provided a wooden stool with wooden bars underneath for the chick to perch on and hide, the parents secretly came on the fourth day, to feed their chick with insects. They even cleaned the chick’s excreta from the balcony floor! I gave the chick ripe bananas as food. In the night I kept the young bird covered with woolen cloth in a shoe box and let it out only when the day became warmer. I found the chick responding to the adult barbet’s calls by turning its head to the direction of the call and could feel the vibration of its body while holding it, with the corresponding movements of the skin of the lower mandible and throat without making any sound even though it was capable of making loud sounds. After eight days, on 13/06/2018 when it was ready to fledge the parents took the chick with them.

Conclusion

The barbets need dead trees or dead branches for building nest holes. In order to build a breeding nest, it prefers a dead tree with some canopy around it. The canopy not only protects the nest from predators but also provides branches for the chick to land when it takes its first flight. If the canopy is too far away the chick may not have a near enough branch to land on and may fall down in between. Such fallen chicks will then be a meal for the feral cats, dogs, Indian grey mongoose Herpestes edwardsii or for birds of prey like Shikra, kites, crows, owls, etc. By cutting down dead trees or deforesting, the barbets end up losing important nesting niches in the habitat which are necessary for breeding.

Acknowledgments:

I am very thankful to Praveen, J. for his great help in preparing this article. Dr. H. S. A. Yahya was very kind in providing me with the necessary information about his research on barbets.

References:

Ali, Salim & Ripley, S. D. (1987). Compact handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan together with those of Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan & Sri Lanka. Oxford University Press, Pp-i-xlii, 11, 1-737, 5211.

Baker, E. C. S. (1925). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon & Burma: Birds, Vol. 4 (2nd ed.), Taylor and Francis, London. 114p.

Baker, E. C. S. (1934). The Nidification of Birds of the Indian Empire. Vol. 3, Taylor and Francis, London, 568p.

Birdlife International (2012). “Psilopogon viridis”. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 Nov 2013.

Blanford, W. T. (1895). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Vol. 3. Taylor and Francis, London. pp.89-90.

den Tex, R. J. & Leonard, J. A. (2013). A molecular phylogeny of Asian barbets speciation and extinction in the tropics. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 68(1): 1-13.

Dickinson, E. C. & Remsen, J. V. Jr. (2013). The Howard and Moore Complete Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-passerines. Aves-Press, Eastbourne, UK, 512p.

Feinstein, J., Yang, X. J. & Li, S. H. (2008). Molecular systematics and historical biogeography of the black-browed barbet species complex (Megalaima oorti). Ibis, 150(1): 40-49.

Hume, A. O. (1890). The nests and eggs of Indian Birds.Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). R. H. Porter, London.

Koh, C. N. & Lu, F. C. (2009). Preliminary investigation on nest-tree and nest-cavity characteristics of the Taiwan Barbet (Megalaima nuchalis) in Taipei Botanical Garden. Taiwan Journal of Forest Science, 24(3): 213-219.

Lin, S.Y., Lu, F. C., Shan, F. H., Liao, S. P., Weng, J. L., Cheng, W. F. & Koh, C. N. (2010). Breeding biology of the Taiwan barbet in Taipei Botanical Garden, Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 122(4): 681-688.

Moyle, R. G. (2004). Phylogenetics of barbets (Aves: Piciformes) based on nuclear and mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 30: 187-200.

Neelakantan, K. K. (1964).”The roosting habits of the barbet”. Newsletter for Birdwatchers, 4(2): 1-2.

Neelakantan, K. K. (1964). “The Green Barbet – M. viridis” Newsletter for Birdwatchers, 4(4): 6-7.

Neelakantan, K. K. (1964). “More about the Green Barbet – M. viridis” Newsletter for Birdwatchers, 4(9): 5-7.

Pande, Satish., Tambe, Saleel., Francis, Clement. M. & Sant, Niranjan. (2003). Birds of Western Ghats, Kokan and Malabar (Including birds of Goa). 16 pr.ll., 1–377. Bombay Natural History Society, Oxford University Press, Mumbai.

Trounov, V. L. & Vasilieva, A. B. (2014): First record of the nesting biology of the red-vented barbet, Megalaima lagrandieri (Aves: Piciformes: Megalaimidae), an Indochinese endemic, Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 62: 671-678.

Yahya, H. S. A. (1989). Breeding biology of Barbets, Megalaima spp. (Capitonidae: Piciformes) at Periyar Tiger Reserve, Kerala. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 85(3): 493–511.

Yahya, Hafiz, S. A. (2000). Food and feeding habits of Indian Barbets, Megalaima spp. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 97(1): 103–116.

Yahya, H. S. A. (2001). Biology of Indian Barbets. Authors Press, New Delhi/Netherland (2nd edition, 2013).